Article: Nature’s Gradients: The Violin Bridge and The Art of Seamless Transition

Nature’s Gradients: The Violin Bridge and The Art of Seamless Transition

When a violin or a cello sings, two worlds speak to one another. The world of structure—maple carved into the bridge, stiff enough to bear hundreds of pounds of string tension—and the world of resonance—spruce thin enough to vibrate like a membrane of breath. These two must meet without conflict. Every note depends on their uneasy friendship.

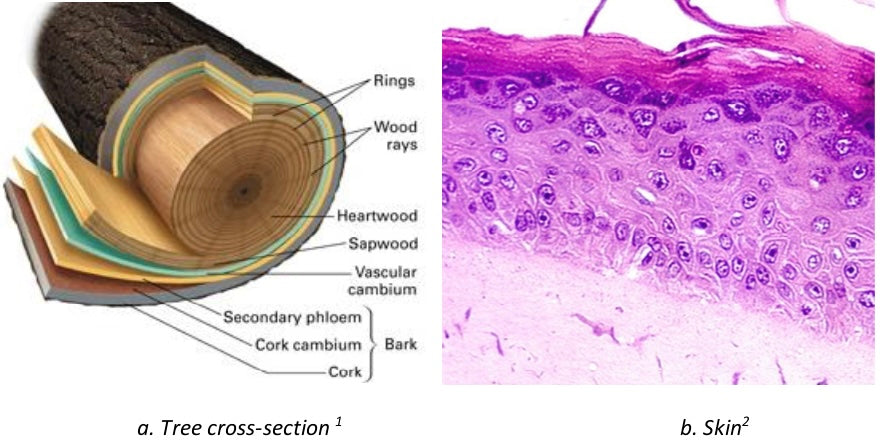

For centuries, instrument makers have joined these woods as if repeating a natural law. Maple and spruce, dense and light, rigid and yielding. Yet nature herself never joins her materials so abruptly. She grades, blends, and transitions. The more closely we study the anatomy of living beings, the more it seems that the cello—though born from wood and wisdom—still bears the signature of analytical, mechanical thinking. It is beautiful, but discretized: one material stops, another begins. Nature does not work this way.

Nature’s Gradients: The Art of Seamless Transition

Consider the human knee. Bone and cartilage meet there, but not by a sudden boundary. Instead, collagen fibers and calcium crystals gradually mingle through a transition zone. The stiff mineral lattice of bone imperceptibly gives way to the springy network of cartilage. The transition spreads stress and preserves motion; it prevents the violent failure that would come from a sharp join.

Or think of the human ear. The cochlea, a spiral of delicate tissue, varies in stiffness from base to apex. That gradient is what allows it to separate sound frequencies—high notes where the structure is firm, low notes where it is soft. The body literally “tunes” its materials across space. Resonance and rigidity exist as a continuous field, not as parts assembled.

Tendons and muscles do something similar. The tendon’s collagen fibers blend into the muscle’s contractile proteins, creating an elastic handshake between pull and resistance. Nowhere does nature draw a hard line. Instead, she builds transitions—microcosms of negotiation between stability and motion.

The Cello as a Biological Metaphor

If nature had built a cello, she would not have chosen separate maple and spruce blocks. She would have grown the bridge out of the top plate, shifting its density molecule by molecule until it became firm enough to hold the strings yet supple enough to breathe with vibration. That imagined instrument would not be assembled—it would develop.

This is where philosopher of biology Henri Bergson becomes crucial. In his 1907 book Creative Evolution, Bergson argues that life itself evolves through canalization—a directed but flexible flow of creative energy (élan vital). Nature’s intelligence, for him, lies not in designing finished objects but in generating continuous transitions. Living form, unlike mechanical form, is never an assembly but a duration—a movement solidified in matter.

For Bergson, the human intellect excels at working with inert solids and fixed geometries. But life’s intelligence—the intelligence of the body—is something else entirely. It knows how to join disparate qualities without rupture. What we call “instinct” in animals, Bergson saw as a kind of sympathy with life’s own movement.

The luthier’s intuition, when he “listens to the wood,” is an echo of this instinctual knowing. He shapes by ear and touch, not by equation. Yet even the best maker must still obey the constraints of his materials and tools. His maple bridge and spruce plate remain separate species. The task ahead, both philosophical and technological, is to let our making rediscover nature’s continuity.

Intelligent Matter: Simondon and the Self-Organizing Object

The French philosopher of technology Gilbert Simondon described this process as individuation—the way a technical object evolves toward internal coherence, where every part resonates with the others. A machine or tool matures when it behaves less like an assembly and more like an organism. The goal is not simply efficiency, but harmony between function and form.

If we apply Simondon’s idea to the cello, its next evolution would not be a new model but a new mode of being. Its parts would not be joined; they would differentiate from one another naturally, like tissues in an embryo. Modern material science, inspired by biology, is already moving in this direction—creating “functionally graded materials” whose stiffness, porosity, and density vary continuously through their volume. These are not manufactured; they are grown by algorithms and feedback, more like coral than carpentry.

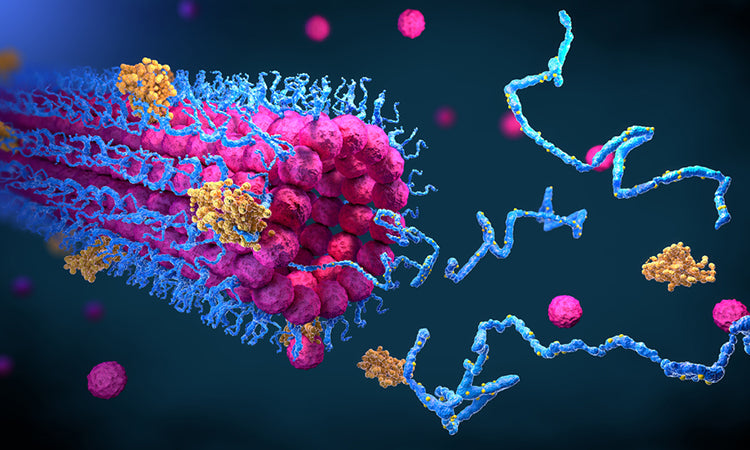

Machine Learning as Synthetic Instinct

Artificial intelligence, especially in the form of machine learning, unexpectedly brings us closer to this biological logic. A learning algorithm does not reason abstractly—it adapts to the patterns in its data. It senses structure, tunes itself, and learns without explicit rules. In that sense, AI functions as a kind of synthetic instinct.

This parallels the work of the police dog whose olfactory intelligence surpasses any man-made sensor. The dog’s nose and brain process smell as a complex symphony of patterns rather than discrete chemical signals. Its accuracy comes from embodied learning—the same principle that guides deep neural networks as they recognize faces, voices, or gestures.

Both the dog’s sense of smell and the AI’s recognition ability represent an intelligence that is immersed rather than detached, intuitive rather than analytical. They echo Bergson’s notion that true understanding is not conceptual but participatory—a knowing by being within the flow.

A New Craft: From Assembly to Evolution

Imagine, then, a cello bridge designed not by human calculation but by a system that learns from the physics of vibration—an AI that, through millions of iterations, discovers the same kind of graded continuity nature uses in bone and cartilage. The result would not be a traditional bridge but a biological one: dense where needed, flexible where necessary, acoustically alive in every cell.

This would not mean abandoning tradition. It would mean fulfilling it. The master luthiers of Cremona, working by ear and intuition, were already following nature’s laws. Their craft was biological in its spirit. What we can do now—with sensors, simulation, and AI—is extend that intuition into matter itself.

The philosopher of biology Henri Bergson would have seen this as the continuation of life’s own creative impulse—the élan vital expressed through human hands and digital tools. Philosopher of technology Gilbert Simondon would call it the individuation of the technical object—the moment when craft, biology, and computation form a single living system.

The Meaning of the Bridge

The cello bridge, in this new light, is not a fixed design but a metaphor for consciousness itself: a tensioned mediator between structure and song, between what resists and what resonates. Our task as makers, scientists, and thinkers is to learn again how to build as nature does—through transitions, not boundaries; through evolution, not assembly.

When that happens, craft will no longer be a human activity opposed to nature, but a continuation of it. The next great instrument will not be a machine or a monument to analysis. It will be something that learns to live.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.